Dystopian Discussions Final Project |

The Real-Life Apocalypses That Inspired Our Authors

Welcome to the final installment of the Dystopian Discussions series. All throughout my time reading and analyzing these apocalypse narratives, I have wondered how the authors came up with such fantastical realities. What ideas informed their versions of the end of the world?

And the hunt was on… To explore this topic, I decided to find as much as I could on where the authors got their inspiration and explore the real-world apocalyptic events that influenced their novels.

I have found that our authors draw from significant pieces of historical apocalyptic literature—religious text that document apocalypses from ancient times as well as prophesy disasters for the future.

Most notably, our authors have recreated elements of real-life apocalypses in their fictional realities. A plethora of catastrophes have devastated humankind across our history—wars, pandemics, tempests, famines, and the list could go on. The authors of our novels find inspiration from these past disasters, but they also consider the apocalypse of the individual. This is usually a world-shattering crisis for one particular person or group of people. Localized calamities such as hurricanes or epidemics fall in this subset as well as personal apocalypses experienced at major points of change and tragedy. We will explore all of these days of reckoning as we look through each novel and the apocalypses that have shaped them…

And the hunt was on… To explore this topic, I decided to find as much as I could on where the authors got their inspiration and explore the real-world apocalyptic events that influenced their novels.

I have found that our authors draw from significant pieces of historical apocalyptic literature—religious text that document apocalypses from ancient times as well as prophesy disasters for the future.

Most notably, our authors have recreated elements of real-life apocalypses in their fictional realities. A plethora of catastrophes have devastated humankind across our history—wars, pandemics, tempests, famines, and the list could go on. The authors of our novels find inspiration from these past disasters, but they also consider the apocalypse of the individual. This is usually a world-shattering crisis for one particular person or group of people. Localized calamities such as hurricanes or epidemics fall in this subset as well as personal apocalypses experienced at major points of change and tragedy. We will explore all of these days of reckoning as we look through each novel and the apocalypses that have shaped them…

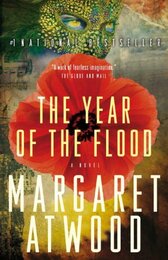

Margaret Atwood's The Year of the Flood

Margaret Atwood brings to life a dystopian reality that she believes may be a plausible version of the future. Ursula Le Guin, in article for The Guardian, offers a thorough summary of The Year of the Flood while challenging Atwood’s claim that her novel is not science fiction. Atwood explains that science fiction is "fiction in which things happen that are not possible today". Rather, Atwood’s story is a potential reality toward which the world is heading. Le Guin helps to identify some of the apocalypses that have inspired Atwood:

“We will gather that it was a Dry Flood, and that the term refers to the extinction of - apparently - all but a very few members of the human species by a nameless epidemic. The nature and symptoms of the disease, aside from coughing, are undescribed. One needs no description of such events when they are part of history or the reader's experience; a reference to "the Black Plague" or "the swine flu" is enough.”

Pandemics of the past are difficult to miss when one imagines where Atwood got her idea for the virus that killed nearly the entire population of earth. The Black Plague cost Europe about one third its total population. The swine flu was not quite so dramatic, but it is nonetheless a shared experience across the world. If we don’t already know someone who contracted the disease, most of us remember hearing about it on the news and getting a swine flu vaccine somewhere along the line.

Le Guin also mentions a Dry Flood and a nameless epidemic. Atwood reveals in an interview with Leonard Lopate from WNYC that Atwood these allude to events in the bookends of the Christian scriptures, Genesis and Revelation. She explains the connection of the Waterless Flood to Noah’s Flood found in Genesis 6-8 when God chooses to enact judgment on the great wickedness of the human race by flooding the earth and destroying all that is in it, but he promises never to flood the earth again.

Click this link to watch the video of Atwood's interview with Leonard Lopate.

Later, the book of Revelation and other passages prophesy destruction at the end times and a Peaceable Kingdom that will rise afterward. Based off of these ideas from the Bible, God’s Gardeners predicted an unknown catastrophe that would kill nearly the whole human race just as Noah’s flood had. They predicted from warnings of pestilence in the book of Revelation that it would take the form of an especially virulent disease…And they were right.

“We will gather that it was a Dry Flood, and that the term refers to the extinction of - apparently - all but a very few members of the human species by a nameless epidemic. The nature and symptoms of the disease, aside from coughing, are undescribed. One needs no description of such events when they are part of history or the reader's experience; a reference to "the Black Plague" or "the swine flu" is enough.”

Pandemics of the past are difficult to miss when one imagines where Atwood got her idea for the virus that killed nearly the entire population of earth. The Black Plague cost Europe about one third its total population. The swine flu was not quite so dramatic, but it is nonetheless a shared experience across the world. If we don’t already know someone who contracted the disease, most of us remember hearing about it on the news and getting a swine flu vaccine somewhere along the line.

Le Guin also mentions a Dry Flood and a nameless epidemic. Atwood reveals in an interview with Leonard Lopate from WNYC that Atwood these allude to events in the bookends of the Christian scriptures, Genesis and Revelation. She explains the connection of the Waterless Flood to Noah’s Flood found in Genesis 6-8 when God chooses to enact judgment on the great wickedness of the human race by flooding the earth and destroying all that is in it, but he promises never to flood the earth again.

Click this link to watch the video of Atwood's interview with Leonard Lopate.

Later, the book of Revelation and other passages prophesy destruction at the end times and a Peaceable Kingdom that will rise afterward. Based off of these ideas from the Bible, God’s Gardeners predicted an unknown catastrophe that would kill nearly the whole human race just as Noah’s flood had. They predicted from warnings of pestilence in the book of Revelation that it would take the form of an especially virulent disease…And they were right.

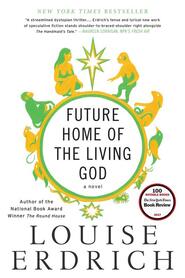

Louise Erdrich's Future Home of the Living God

There are two sides to the apocalypse as imagined by Louise Erdrich in Future Home of the Living God—the evolutionary retrograde of all living organisms and a dystopian government system that wields authoritarian control over society, the Church of the New Constitution. While evolution reversing itself is a fictional fabrication (at least I certainly hope so), government surveillance is definitely not. In the novel, the government uses spine-chilling surveillance tactics to uncover pregnant women. Any pregnant woman discovered was forcibly taken to government-controlled hospitals where she would be confined and monitored. After delivering their babies, the mothers would often die, if their babies survived the birth, they would be held and studied.

Erdrich drew inspiration for her story from familiar dystopian aspects of the present day. In an email written to Vanity Fair, Erdrich says, “So many of the troops in Iraq and Afghanistan were from my home state: North Dakota. I simply felt that we were plunging toward a selective dystopia. And, indeed, for those who have suffered and still suffer in the ongoing war, the fallout is often a personal dystopia.” Future of Home of the Living God traces its origins to the war on terrorism and the government surveillance that burgeoned over the past two decades. The Vanity Fair article continues Erdrich’s line of reasoning,

“Benign technology becoming sinister is a recurring threat of the Internet era, and is a concern that Erdrich has herself. “We are dominated by a handful of giant corporations which are now considered individuals, and which track our every purchase, know our whereabouts, can pick out our features in a crowd. . . all of this has happened so quickly, and under the guise of keeping us happy and safe,” she notes. “It’s much scarier than anything in my book.”

The American government today uses technology and communications to invade its citizens’ privacy. The New York Times archives compiled a timeline of government surveillance policy developments. This timeline highlights disturbing surveillance tactics, such as warrantless eavesdropping on calls and mass collection of metadata.

The New York Times continues to help readers understand the surveillance from corporations in this article by Tim Herrara. The author describes receiving a 400-page file on himself from a company he had never heard of. Herrara was shocked to find that the file included specific and personal details, like conversations with AirBnB hosts. I often struggle to grasp what the big deal is, but Herrara provides an astute perspective: “I think the bottom line is that it’s creepy at best. It enables manipulative advertising and political messaging in ways that make it a lot easier for the messengers to be unaccountable. It enables discriminatory advertising without a lot of accountability, and in the worst cases it can put real people in real danger.”

In addition to alarming invasion of privacy, the novel features Native Americans, whom have suffered extreme cataclysmic events. Many characters in the novel are members of the Ojibwe tribe. Erdrich colors Future Home of the Living God with history of the persecution that European colonists inflicted on American indigenous peoples. Eddy and other tribesmen want to take advantage of arrival of dystopia and the flight of the masses from their homes surrounding the Ojibwe reservation. On page 213 of the novel, they devise a plan to repossess the land “lost through incremental treaties then sold off in large part when the Dawes Act of 1862 removed land from communal ownership.”

The history of Native Americans is indubitably apocalyptic. History.com shares an eye-opening summary of American indigenous sufferings. Native Americans were desolated by new diseases carried by European settlers. Then they suffered over 1,500 government-authorized wars, attacks, and raids. The racial genocide dwindled their numbers from 5-15 million to merely 238,000. I did not find Erdrich mention the historical apocalypse of the Native Americans in her interviews, but it played a significant role in shaping Future Home of the Living God.

Erdrich drew inspiration for her story from familiar dystopian aspects of the present day. In an email written to Vanity Fair, Erdrich says, “So many of the troops in Iraq and Afghanistan were from my home state: North Dakota. I simply felt that we were plunging toward a selective dystopia. And, indeed, for those who have suffered and still suffer in the ongoing war, the fallout is often a personal dystopia.” Future of Home of the Living God traces its origins to the war on terrorism and the government surveillance that burgeoned over the past two decades. The Vanity Fair article continues Erdrich’s line of reasoning,

“Benign technology becoming sinister is a recurring threat of the Internet era, and is a concern that Erdrich has herself. “We are dominated by a handful of giant corporations which are now considered individuals, and which track our every purchase, know our whereabouts, can pick out our features in a crowd. . . all of this has happened so quickly, and under the guise of keeping us happy and safe,” she notes. “It’s much scarier than anything in my book.”

The American government today uses technology and communications to invade its citizens’ privacy. The New York Times archives compiled a timeline of government surveillance policy developments. This timeline highlights disturbing surveillance tactics, such as warrantless eavesdropping on calls and mass collection of metadata.

The New York Times continues to help readers understand the surveillance from corporations in this article by Tim Herrara. The author describes receiving a 400-page file on himself from a company he had never heard of. Herrara was shocked to find that the file included specific and personal details, like conversations with AirBnB hosts. I often struggle to grasp what the big deal is, but Herrara provides an astute perspective: “I think the bottom line is that it’s creepy at best. It enables manipulative advertising and political messaging in ways that make it a lot easier for the messengers to be unaccountable. It enables discriminatory advertising without a lot of accountability, and in the worst cases it can put real people in real danger.”

In addition to alarming invasion of privacy, the novel features Native Americans, whom have suffered extreme cataclysmic events. Many characters in the novel are members of the Ojibwe tribe. Erdrich colors Future Home of the Living God with history of the persecution that European colonists inflicted on American indigenous peoples. Eddy and other tribesmen want to take advantage of arrival of dystopia and the flight of the masses from their homes surrounding the Ojibwe reservation. On page 213 of the novel, they devise a plan to repossess the land “lost through incremental treaties then sold off in large part when the Dawes Act of 1862 removed land from communal ownership.”

The history of Native Americans is indubitably apocalyptic. History.com shares an eye-opening summary of American indigenous sufferings. Native Americans were desolated by new diseases carried by European settlers. Then they suffered over 1,500 government-authorized wars, attacks, and raids. The racial genocide dwindled their numbers from 5-15 million to merely 238,000. I did not find Erdrich mention the historical apocalypse of the Native Americans in her interviews, but it played a significant role in shaping Future Home of the Living God.

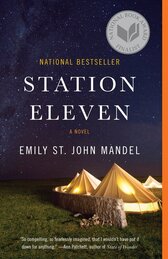

Emily St. John Mandel's Station Eleven

The real-life apocalypses that formed Emily St. John Mandel’s vision for Station Eleven clearly have something to do with widespread disease. The catastrophic pandemics in human history remain a classic influence for the genre of apocalypse. An article from MPHonline lists the most devastating pandemics to plague the human race. These include the Black Death of the 14th century, which resulted in approximately 75-200 million deaths, the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, which resulted in 20-50 million deaths, and the HIV/AIDS pandemic at its height from 2005-2012, that has caused 36 million deaths and counting.

St. John Mandel brings the reality of a pandemic to a terrifying extreme. Nearly the entire human race succumbs to the Georgian flu in a matter of a few weeks. In Station Eleven, St. John Mandel illustrates the failure of most all electronics and technological advances. St. John Mandel tells Eliza Borné in an interview with Bookpage:

“Early on, I came across a faux-documentary that was produced by the History Channel, which outlined what might happen if a catastrophic pandemic were to hit the United States…There were a lot of details that I hadn’t previously considered, like how quickly the grid would go down if people stop going to work in power plants.”

One fascinating inspiration for Station Eleven and St. John Mandel’s dive into the post-apocalypse is the grim and hopeless outlook humankind has had for centuries. She discusses this perspective in an interview with Adam Byko for UCF Today. Byko asks how the phrase “Survival is insufficient” has influenced her as an artist considering the concerning changes in the world since the book was published in 2014. St. John Mandel responds, “you can make an argument that the world’s become more bleak, but I feel like we always think we’re living at the end of the world. You know, when have we ever felt like it wasn’t going to be catastrophic?”

This comment struck me as profound and familiar. All of my life, I have heard conversations on how close we are to disaster or the end of the world. It comes up in church, in the news, and even back in my high school science classes. I mentioned this to my father and he said he experienced hearing that same attitude his whole life. I imagine my grandparents, who were born during the Great Depression, would describe something similar throughout their lifetime. They experienced WWII, the Cold War and many turbulent changes—I think it’s safe to say they had a rougher go of things, yet everyone thinks the sky is falling no matter what.

St. John Mandel brings the reality of a pandemic to a terrifying extreme. Nearly the entire human race succumbs to the Georgian flu in a matter of a few weeks. In Station Eleven, St. John Mandel illustrates the failure of most all electronics and technological advances. St. John Mandel tells Eliza Borné in an interview with Bookpage:

“Early on, I came across a faux-documentary that was produced by the History Channel, which outlined what might happen if a catastrophic pandemic were to hit the United States…There were a lot of details that I hadn’t previously considered, like how quickly the grid would go down if people stop going to work in power plants.”

One fascinating inspiration for Station Eleven and St. John Mandel’s dive into the post-apocalypse is the grim and hopeless outlook humankind has had for centuries. She discusses this perspective in an interview with Adam Byko for UCF Today. Byko asks how the phrase “Survival is insufficient” has influenced her as an artist considering the concerning changes in the world since the book was published in 2014. St. John Mandel responds, “you can make an argument that the world’s become more bleak, but I feel like we always think we’re living at the end of the world. You know, when have we ever felt like it wasn’t going to be catastrophic?”

This comment struck me as profound and familiar. All of my life, I have heard conversations on how close we are to disaster or the end of the world. It comes up in church, in the news, and even back in my high school science classes. I mentioned this to my father and he said he experienced hearing that same attitude his whole life. I imagine my grandparents, who were born during the Great Depression, would describe something similar throughout their lifetime. They experienced WWII, the Cold War and many turbulent changes—I think it’s safe to say they had a rougher go of things, yet everyone thinks the sky is falling no matter what.

Omar El Akkad's American War

The American Civil was no doubt one of the most apocalyptic events that the United States has ever suffered. The National Archives claims,

“The Civil War had a greater impact on American society and the polity than any other event in the country’s history. It was also the most traumatic experience endured by any generation of Americans. At least 620,000 soldiers lost their lives in the war, 2 percent of the American population in 1861. If the same percentage of Americans were to be killed in a war fought today, the number of American war dead would exceed 6 million.”

Not only did the war kill a staggering portion of the population, it injured hundreds of thousands more as well as wreaked havoc on the land and infrastructure of the nation.

Omar El Akkad applies the horror of the American Civil War to his novel. he reawakens the wars themes, such as polarity of the North and South ideologies, Southern rebellion, destruction of the land, and the slaughtering of innocent citizens. However, El Akkad’s influences were much broader than just the War Between the States. Take a look at this video from an interview with Pac Macmillan: Omar El Akkad on inspiration for American War

As El Akkad states, he takes “conflicts that have happened very far away and to people who don’t have much of a voice, and recasts them as elements very close to home.” He names the United States’ occupation of Afghanistan to highlight injustice around the world. CBC Books illuminates more on the author’s thought process:

"I wrote American War to talk about this idea of there being no such thing as a foreign kind of suffering, that the way we react to injustice is universal. We just happen to live in a relatively peaceful part of the world and so we have this privilege of assuming that those people all the way over there are behaving in some kind of fundamentally exotic way, and American War is a lot about this idea that that's simply not true, that we all react to injustice the same way."

Similar to Atwood’s The Year of the Flood, El Akkad’s narrative deals with the threat of a climate apocalypse. The Second American Civil War sparks from southern rebellion against the government’s prohibition of fossil fuel usage. Just as slavery was a foundational aspect of the economy and livelihood of the South, fossil fuels were viewed as essential in American War. A climate-induced collapse is a very tangible fear today. This Wikipedia article catalogues popular predictions of an apocalypse the world could experience as soon as 2050—just 29 years from now! The consequences will include “radical destabilization of life on earth due to crop failures, fires, crashing economies, flooding, and hundreds of millions of climate refugees” according to the article.

Colson Whitehead's Zone One

Zone One by Colson Whitehead creates a bit of a challenge as far as discussing the real-world apocalypses that shape the novel. Out of all the apocalypses presented in our texts, a zombie apocalypse may be the least likely to actually occur. Of course, Whitehead’s writing goes much deeper than imaginary monsters. Whitehead weaves the notion of a personal apocalypse into the fabric of his narrative. This theme creates significance for the seemingly harmless straggler zombies. Whitehead shares in an article with The Atlantic about the meaning of the stragglers, when he says, “They're the living dead. They share a lot of characteristics with ghosts—people who can't progress to the next stage. That notion of the ghost applies to both the stragglers and the remaining human survivors.”

We are all familiar with the tragedy of a person who goes through the motions of life without really living. I think the best picture of state of mind can be found in Disney’s movie Soul. The movie introduces characters called “lost souls” who are trapped in their depression or anxiety. They could also be a workaholic, like the movie’s character that is utterly consumed by his stock market job. The movie characterizes this man by exhaustion and fear, chained to his desk and obsessed with his efforts to “make a trade.”

Watch this short clip to see how Disney creates the idea that these people are lost because they have actually lost their souls. When the man regains his soul, he asks, “What am I doing with my life?” and encourages his coworkers to free themselves.

Emily St. John Mandel echoes the apocalypse of “losing one’s soul” in Station Eleven. The character Clark has a career in 360° assessments of corporations. The assessments revolve around “the target”, an executive whom the client company hopes to improve. Clark interviews an employee of his client company, Dahlia, who has ideas unusual ideas about her boss and the corporate world in general. Dahlia tells Clark on page 162 of Station Eleven that her boss may change a little with the coaching from the 360° assessment, but “he’ll still be a successful-but-unhappy person who works until 9 p.m. every night because he’s got a terrible marriage and doesn’t want to go home…who just seems like he wishes he’d done something different with his life.” Dahlia’s next thought resonates deeply with Whitehead: “it’s like the corporate world’s full of ghosts…maybe a fairer way of putting this would be to say that adulthood’s full of ghosts” (163).

Ghosts. Just like the stragglers that mindlessly repeat the same activity without ceasing. It is a picture of personal apocalypse—living a life without meaning or purpose.

We are all familiar with the tragedy of a person who goes through the motions of life without really living. I think the best picture of state of mind can be found in Disney’s movie Soul. The movie introduces characters called “lost souls” who are trapped in their depression or anxiety. They could also be a workaholic, like the movie’s character that is utterly consumed by his stock market job. The movie characterizes this man by exhaustion and fear, chained to his desk and obsessed with his efforts to “make a trade.”

Watch this short clip to see how Disney creates the idea that these people are lost because they have actually lost their souls. When the man regains his soul, he asks, “What am I doing with my life?” and encourages his coworkers to free themselves.

Emily St. John Mandel echoes the apocalypse of “losing one’s soul” in Station Eleven. The character Clark has a career in 360° assessments of corporations. The assessments revolve around “the target”, an executive whom the client company hopes to improve. Clark interviews an employee of his client company, Dahlia, who has ideas unusual ideas about her boss and the corporate world in general. Dahlia tells Clark on page 162 of Station Eleven that her boss may change a little with the coaching from the 360° assessment, but “he’ll still be a successful-but-unhappy person who works until 9 p.m. every night because he’s got a terrible marriage and doesn’t want to go home…who just seems like he wishes he’d done something different with his life.” Dahlia’s next thought resonates deeply with Whitehead: “it’s like the corporate world’s full of ghosts…maybe a fairer way of putting this would be to say that adulthood’s full of ghosts” (163).

Ghosts. Just like the stragglers that mindlessly repeat the same activity without ceasing. It is a picture of personal apocalypse—living a life without meaning or purpose.

Tom Sweterlitsch's The Gone World

Both Emily St. John Mandel and Tom Sweterlitsch comment on a popular attitude in society that the world is coming to and end. He found inspiration to write a novel related to the apocalypse genre from the dystopia of everyday life. Similar to St. John Mandel’s feeling that society always seems to think it’s the end of the world, Sweterlitsch tells Amy Brandy in an interview with Shelf Awareness,

“We're undoubtedly living in a dystopian and apocalyptic time. For many years, racial minorities and the poor have already been living in dystopian America, and now, with every news cycle, it's easier to imagine apocalyptic nuclear devastation. Both subgenres address a fear that the pleasures of life and the institutions that protect our safety and happiness are false or fragile and can easily disappear.”

Sweterlitsch’s novel has conspicuous ties to Christianity. There are a plethora of other Christian themes, symbols, and allusions throughout the novel. Nestor asks Shannon near the beginning of the story if she believes in the resurrection of the body—this foreshadows the figurative resurrection of echoing. At Nestor’s house, Shannon notices a painting of Jesus dead right after being taken off the cross. Karl Hyldekrugger, the character behind multiple murders and acts of torture, is referred to as “the Devil”. Nestor also compares the Terminus to hell.

Sweterlitsch has had religious influences in his life that have contributed to the Christian themes in The Gone World. He describes his inspiration as follows:

“I'm inspired by my father-in-law, Dr. Howard Brandt, who was a brilliant theoretical physicist in the fields of quantum cryptology and quantum computing for the Department of Defense, but also--and this is somewhat unusual in the sciences--he was a man of great religious faith. He was demanding and rigorous in his science, but his faith gave him humility that what we know about the universe is only a fraction of the truth.”

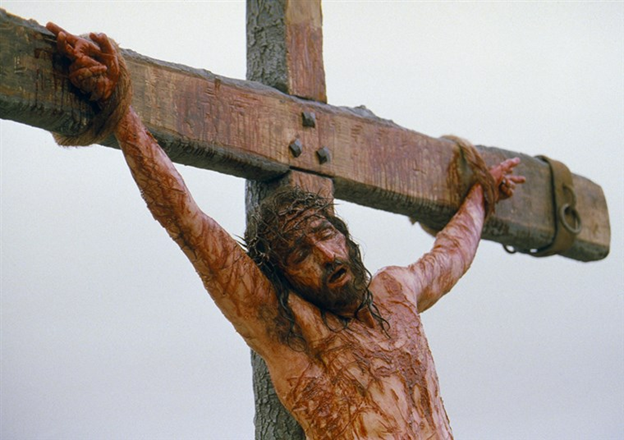

The Bible includes one of the first apocalyptic narratives ever in the book of Revelation. I would argue, however, that the biblical apocalypse most heavily featured in The Gone World is Jesus’ crucifixion. This event was world-shattering to his disciples who understood Jesus was God himself in the form of a human. Before his resurrection, his followers must have been overwhelmed with doubts and sorrow.

An interesting teaching that Sweterlitsch develops in his novel is that the Christian is figuratively crucified with Christ to symbolize atonement from their sin. The apostle Paul writes in Galations 2:20, “I have been crucified with Christ; and it is no longer I who live, but Christ lives in me; and the life which I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave Himself up for me.” The idea also appears in Romans 6:5-6: “For if we have become united with Him in the likeness of His death, certainly we shall also be in the likeness of His resurrection, knowing this, that our old self was crucified with Him, in order that our body of sin might be done away with.”

This biblical teaching takes a literal manifestation in Sweterlitsch’s novel. When the Terminus comes, people are lifted into the air as if they are being crucified upside down. As the Terminus is compared to hell, the crucifixions seem like a torturous perversion of the second coming of Christ when believers in Christ will be lifted into the air to be with him.